Linear Models (Again)

This lab script teaches the implementation and interpretation of the basic linear model by reference to Braithwaite’s (2006) analysis of the geographic spread of militarized interstate disputes. Students should read that article to understand the context of what we’re doing. This lab script will just implement one of their basic models and unpack its contents.

# ___

# _.-| | |\__/,| (`\

# { | | |o o |__ _) ) # not again...

# "-.|___| _.( T ) ` /

# .--'-`-. _((_ `^--' /_< \

# .+|______|__.-||__)`-'(((/ (((/

#

# Lab 4b: Linear Models (Again)

If it’s not installed, install it.

library(tidyverse)

#> ── Attaching core tidyverse packages ──────────────────────── tidyverse 2.0.0 ──

#> ✔ dplyr 1.1.4 ✔ readr 2.1.4

#> ✔ forcats 1.0.0 ✔ stringr 1.5.0

#> ✔ ggplot2 3.5.2 ✔ tibble 3.3.0

#> ✔ lubridate 1.9.4 ✔ tidyr 1.3.0

#> ✔ purrr 1.1.0

#> ── Conflicts ────────────────────────────────────────── tidyverse_conflicts() ──

#> ✖ dplyr::filter() masks stats::filter()

#> ✖ dplyr::lag() masks stats::lag()

#> ℹ Use the conflicted package (<http://conflicted.r-lib.org/>) to force all conflicts to become errors

library(stevethemes)

library(stevemisc)

#>

#> Attaching package: 'stevemisc'

#>

#> The following object is masked from 'package:lubridate':

#>

#> dst

#>

#> The following object is masked from 'package:dplyr':

#>

#> tbl_df

Load the data

This code aims to augment what students should’ve already learned in

the previous lesson.

I’ll be repeating myself because repetition will certainly help the

student’s learning, but I hope any terseness (for the moment) is met

with some understanding since it’s a fair bit of work to create new

lessons on the fly. No matter, I hope students have learned by now how

to read data from the internet. I’ve uploaded the data for this session

to Athena (in both forms) and to my website. You have two options here

if you’re going the route of my website. One is the Stata file and the

other is the R serialized data frame (.rds). Let’s go with the R

serialized data frame for this session. If you go this route, you have

to include url() in the readRDS() function. Observe:

Braith <- readRDS(url("https://svmiller.com/extdata/braithwaite2006gsmd.rds"))

# Braith <- haven::read_dta("https://svmiller.com/extdata/braithwaite2006gsmd.dta")

# ^ also works. You can also download a copy of the data fraom Athena.

This part won’t be super fun, but this is the price of doing business in this world. Ideally, you read the article in question to get an idea of what Alex is doing. Joshua Alley has these data in his Github repository of simple cross-sectional OLS data sets. The original data and analyses were conducted in Stata, so some forensics are necessary here based on the Stata .do file that Alex wrote. We’re going for a replication of Table II, so let’s identify what exactly he did and get a reduced version of the data based on Alex’ description and the Stata .do file. I’ll do it for you this session but, in the Master’s level, I’ll ask you to figure stuff out like this yourself. It’s good experience.

Before we begin, though, I welcome anyone in the class as we’re doing this to tell me what this article is about.

Briefly, we’re aiming to reproduce this model, presented below in Stata syntax.

# reg log_radius_area territory logsize host_mt host_for water cwpceyrs bord_vital host_resource if final_hostile>0, robust;

Okay, let’s look at our data…

Braith

#> # A tibble: 296 × 26

#> dispnum dyadid ccode1 ccode2 year logcap_ratio allies joint_democ incidents

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 4327 91093 91 93 2001 0.144 1 1 1

#> 2 4085 437475 437 475 1993 1.92 1 0 1

#> 3 4114 670679 670 679 1994 1.93 1 0 8

#> 4 4191 630640 630 640 1996 0.211 0 0 1

#> 5 4228 365700 365 700 1998 3.71 0 0 3

#> 6 4001 800811 800 811 1994 1.97 0 0 23

#> 7 4225 731740 731 740 1999 1.54 0 0 3

#> 8 4064 710713 710 713 1995 2.47 0 0 16

#> 9 4338 365373 365 373 1999 3.69 1 0 1

#> 10 4086 355705 355 705 1996 0.362 0 0 1

#> # ℹ 286 more rows

#> # ℹ 17 more variables: territory <dbl>, sdd <dbl>, radius <dbl>,

#> # final_hostile <dbl>, jointsize <dbl>, log_radius_area <dbl>,

#> # log_sdd_area <dbl>, pop_dense <dbl>, water <dbl>, logdurat <dbl>,

#> # cwpceyrs <dbl>, host_mt <dbl>, host_for <dbl>, host_resource <dbl>,

#> # bord_vital <dbl>, log_jointsize <dbl>, `_est_model1` <dbl>

names(Braith)

#> [1] "dispnum" "dyadid" "ccode1" "ccode2"

#> [5] "year" "logcap_ratio" "allies" "joint_democ"

#> [9] "incidents" "territory" "sdd" "radius"

#> [13] "final_hostile" "jointsize" "log_radius_area" "log_sdd_area"

#> [17] "pop_dense" "water" "logdurat" "cwpceyrs"

#> [21] "host_mt" "host_for" "host_resource" "bord_vital"

#> [25] "log_jointsize" "_est_model1"

This is a good lesson for those of you who may have some experience with

Stata from another program. Stata will guess stuff on your behalf. R

won’t. In this case, Stata can infer you meant log_jointsize in the

data when you asked for logsize. R 100% won’t do that for you. Beyond

that, reducing the raw data to a simple form for the sake of the

analysis isn’t that hard.

Braith %>%

filter(final_hostile > 0) %>%

select(log_radius_area, territory, log_jointsize,

host_for, host_mt, water, cwpceyrs, bord_vital,

host_resource) -> Data

Data

#> # A tibble: 296 × 9

#> log_radius_area territory log_jointsize host_for host_mt water cwpceyrs

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 4.36 0 12.4 0 0 0 0

#> 2 4.36 0 17.1 0 0 0 1

#> 3 10.7 1 14.7 0.0686 44.2 0 4

#> 4 4.36 0 14.7 1.38 58.2 0 7

#> 5 10.2 0 16.7 0 13.6 0 0

#> 6 11.4 1 13.5 34.7 27.8 0 6

#> 7 4.36 0 13.1 0 0 0 0

#> 8 13.5 1 16.1 22.5 56.0 0 0

#> 9 4.36 0 16.6 10.9 49.2 0 5

#> 10 4.36 0 14.9 1.16 7.71 0 5

#> # ℹ 286 more rows

#> # ℹ 2 more variables: bord_vital <dbl>, host_resource <dbl>

How did we do?

summary(M1 <- lm(log_radius_area ~ territory + host_resource + host_mt +

host_for + water + bord_vital + log_jointsize + cwpceyrs,

data = Data))

#>

#> Call:

#> lm(formula = log_radius_area ~ territory + host_resource + host_mt +

#> host_for + water + bord_vital + log_jointsize + cwpceyrs,

#> data = Data)

#>

#> Residuals:

#> Min 1Q Median 3Q Max

#> -6.192 -2.479 -1.190 2.768 9.494

#>

#> Coefficients:

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> (Intercept) 4.496996 1.948533 2.308 0.021717 *

#> territory 1.624430 0.412026 3.943 0.000101 ***

#> host_resource 0.984149 0.431537 2.281 0.023307 *

#> host_mt 0.025871 0.007775 3.328 0.000990 ***

#> host_for -0.012035 0.007177 -1.677 0.094620 .

#> water -0.600507 0.558129 -1.076 0.282863

#> bord_vital -0.809148 0.407514 -1.986 0.048032 *

#> log_jointsize 0.135650 0.125150 1.084 0.279319

#> cwpceyrs -0.040498 0.012939 -3.130 0.001928 **

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

#>

#> Residual standard error: 3.395 on 287 degrees of freedom

#> Multiple R-squared: 0.1448, Adjusted R-squared: 0.121

#> F-statistic: 6.074 on 8 and 287 DF, p-value: 3.154e-07

Got it. Don’t worry about the difference in the test statistics as we’re not going with robust standard errors for the sake of this exrecise. I explain a bit about what those are here.

Unpacking the Model Output

R presents a summary of the residuals at the top, though our eyes should

go right to the coefficients first (the extent to which we are

interested in hypothesis-testing). In Alex’ case, he’s interested in

explaining the geographic spread of militarized interstate disputes

through a variety of factors. He’s interested first, it seems, in the

pernicious effect of territorial disputes. He hypothesizes that disputes

over the allocation of territory are more likely to be dispersed over a

geographic area than disputes over any other issues. The coefficient for

that territory variable is 1.624. The standard error is .412. Dividing

the coefficient over the standard error for 287 degrees of freedom

results in a test statistic of 3.943. If there were truly no difference

between disputes over territory and disputes over any other issue, the

probability we observed what we observed is .000101. Thus, we reject the

null hypothesis as incompatible with the data we observed and suggest

Alex’ hypothesized relationship is closer to what it truly is. Since the

dependent variable is log-transformed, you’ll want to think of some

creative ways to express this relationship. I discuss these

here.

For example:

- Toggling a dispute from over some other issue to the allocation of

territory multiplies the geographic spread (as measured in the

radius from the center of the dispute to its furthest incident) by

exp(1.624)(about 5.075). - Toggling a dispute from over some other issue to the allocation of

territory results in a

(exp(1.624) - 1)*100(about 407.33) percent increase in the geographic spread of the dispute (as measured by the radius from the center of the dispute to its furthest incident).

Since the coefficient isn’t close to 0, I would advise against using the

rule of thumb of multiplying the coefficient by 100. You could, however,

do that with the forest variable (host_for). Alex doesn’t argue this

point with any obvious emphasis, but his treatment on pp. 510-11 implies

that forest would be impassable terrain. This should constrain the

spread of the dispute and a negative relationship should emerge. He

measures this by the percentage of the territory that is covered in

forest. The coefficient for this is -.012 and is significant at the .10

level in this model without robust standard errors. Thus, you can

communicate the relative change, percentage change, and percentage

change approximations by the following ways:

exp(-0.012035)-1 # relative change

#> [1] -0.01196287

(exp(-0.012035)-1)*100 # percentage change

#> [1] -1.196287

-0.012035*100 # percentage change approximation

#> [1] -1.2035

You can do something similar for the mountainous terrain variable, even as this has a different effect than the one hypothesized by Alex.

exp(0.025871)-1 # relative change

#> [1] 0.02620856

(exp(0.025871)-1)*100 # percentage change

#> [1] 2.620856

0.025871*100 # percentage change approximation

#> [1] 2.5871

If this is a bit much for you at this level, that’s cool too. You can just note what’s significant and in what direction and say something like “a one-unit change in the percentage of the territory that is covered in mountains coincides with an estimated change of .025 in the logged value of the radius between the center of the dispute to the furthest incident.” I’d be remiss, though, if I didn’t give you things to consider.

We should also make an obligatory reference to the stuff included at the bottom of the output. Namely, the adjusted R-squared suggests the model accounts for about 12% of the variation in geographic spread. We’ve also comfortably beat the mean-only model (see: the F-stat).

Again, with the Diagnostics

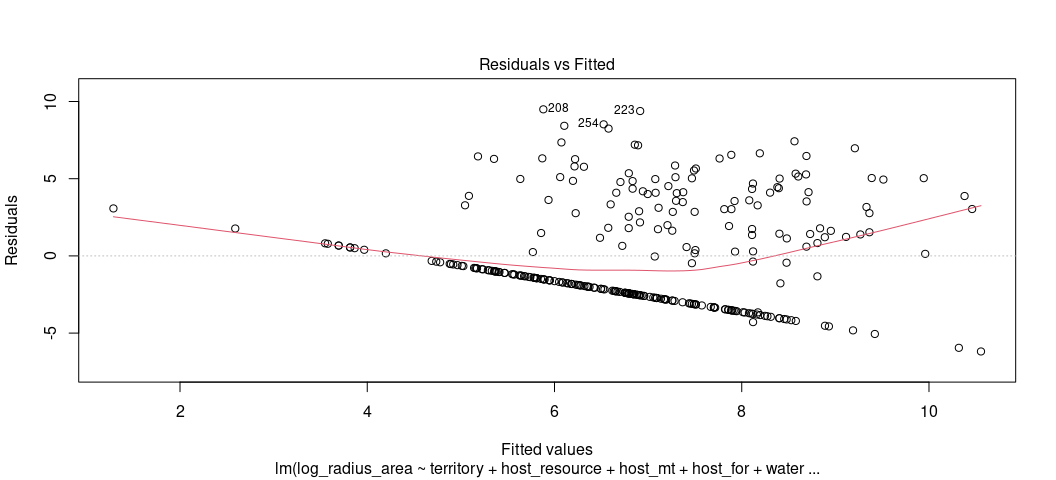

Let’s inspect the model output as we did in the previous lesson. Remember: the fitted-residual plot is the most “bang for your buck” linear model diagnostic. It’s where you should start.

plot(M1, which = 1)

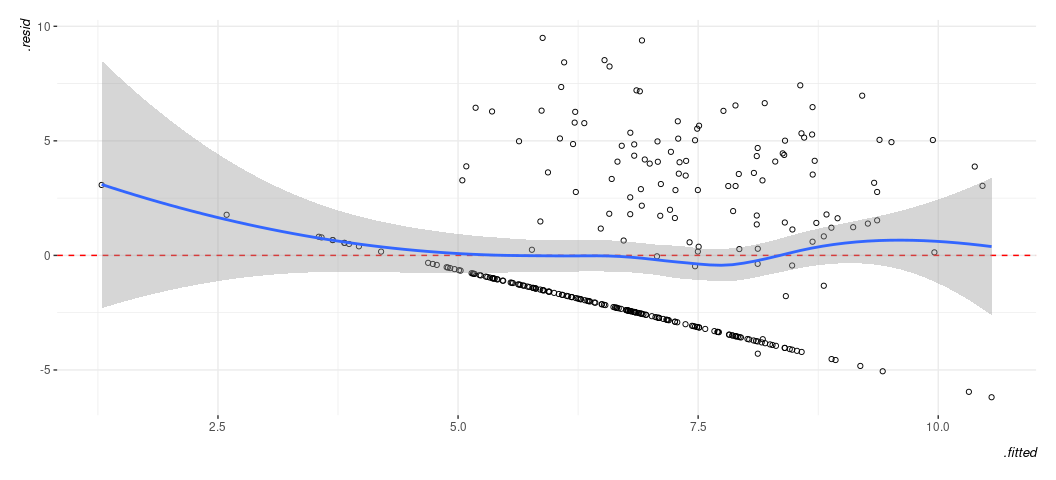

Oh boy… that’s not good. Let’s pretty it up bit, just for presentation

and added exposure to the augment() function in {broom}.

broom::augment(M1) %>%

ggplot(.,aes(.fitted, .resid)) +

geom_point(pch = 21) +

theme_steve(style='generic') +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0, linetype="dashed", color="red") +

geom_smooth(method = "loess")

#> `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

Remember what you should want to see in a fitted-residual plot. Know this isn’t it. That said, here’s what you can discern this is telling you and what it might mean for things you’d want to do with your model.

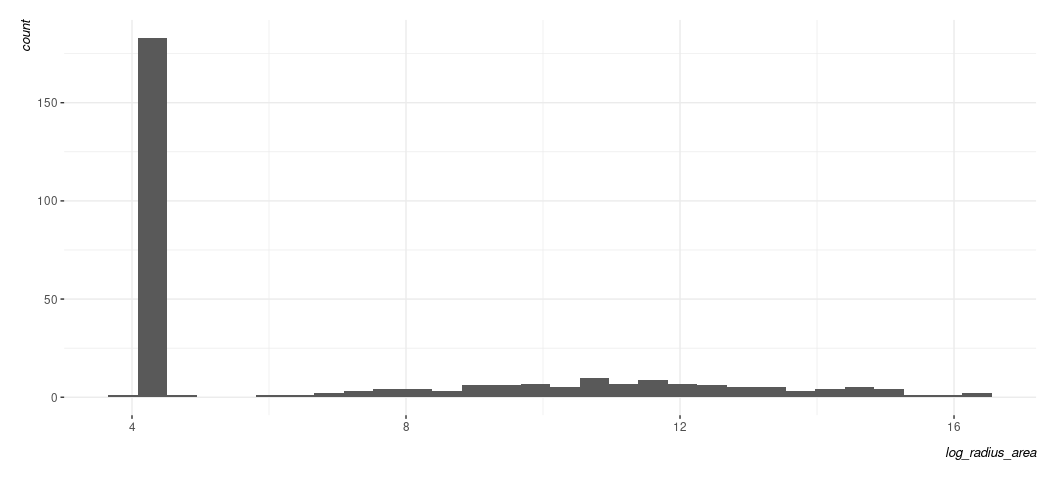

The first thing that grabs your attention is the clear line. Generally, a line like this of any kind in your fitted-residual plot is suggesting some kind of discrete pattern in the DV. Let’s see this for ourselves.

Data %>% ggplot(.,aes(log_radius_area)) +

geom_histogram() +

theme_steve(style='generic')

#> `stat_bin()` using `bins = 30`. Pick better value with `binwidth`.

Data %>% arrange(log_radius_area)

#> # A tibble: 296 × 9

#> log_radius_area territory log_jointsize host_for host_mt water cwpceyrs

#> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl>

#> 1 3.83 1 11.8 75.1 47.0 0 2

#> 2 4.36 0 12.4 0 0 0 0

#> 3 4.36 0 17.1 0 0 0 1

#> 4 4.36 0 14.7 1.38 58.2 0 7

#> 5 4.36 0 13.1 0 0 0 0

#> 6 4.36 0 16.6 10.9 49.2 0 5

#> 7 4.36 0 14.9 1.16 7.71 0 5

#> 8 4.36 0 14.7 0 8.60 0 0

#> 9 4.36 0 12.7 34.0 49.8 1 1

#> 10 4.36 0 13.8 86.8 4.70 0 0

#> # ℹ 286 more rows

#> # ℹ 2 more variables: bord_vital <dbl>, host_resource <dbl>

When you see something like this, it’s suggesting you have some kind of “hurdle” component to the data-generating process. There is a separate process that determines that big bar you see and then a separate one determining the variation in the flatter distribution to the right of it. Braithwaite’s third footnote is pointing to his 2005 data article in International Interactions that might provide more context for why this value of 4.363605 occurs so much in his data. I do not at all expect you to know exactly what to do under these circumstances. That said, here’s about what I’d expect you to say: “the fitted-residual plot suggests a clear discrete pattern in the DV and the histogram suggests two separate data-generating processes. Both strongly imply the linear model is a questionable fit for the data.”

The second thing that grabs your attention (maybe?) is the disagreement

between the LOESS smoother and the flat line at 0. I don’t know if it’s

no. 2, but it’s what we’ll talk about next. When you see something like

this, it’s suggesting some kind of non-linear relationship in the data.

It comes with three major caveats though. The first is that the LOESS

smoother will always come off the line at 0 near the tails of the

fitted-residual plot. Thus, we really shouldn’t say something with any

authority yet. The second is that we obviously have the discrete

clumping we noted above. That might be an important part of this. The

third is that we 100% won’t know where until we looked at something a

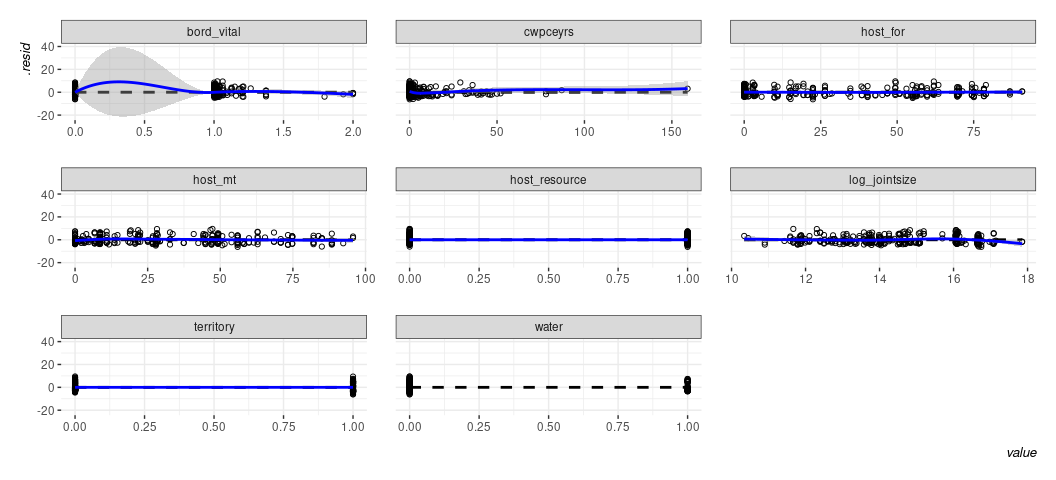

bit more informative. linloess_plot() in {stevemisc} will do this.

linloess_plot(M1, pch=21) +

theme_steve(style='generic')

#> Warning: attributes are not identical across measure variables; they will be

#> dropped

#> `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

#> `geom_smooth()` using formula = 'y ~ x'

Binary IVs will never be the issue here. It’s the “vital border” variable that looks like it has some weirdness. Based on what I remember of Starr (2002) and how Alex describes this on p. 514, it would suggest that the 0s are probably a distinct phenomenon that should be focused on in some detail. Beyond that, it really seems like the fitted-residual plot’s LOESS smoother is really just drawing attention to the “hurdle” component of the DV.

The third thing you can tell from the fitted-residual plot is that the variance of the residuals are clearly fanning out as the fitted values increase. That’s as tell-tale a sign of heteroskedasticity as you’re going to see. It’s also why Alex estimated this model with robust standard errors. If I remember Stata correctly, this is type “HC1”.

lmtest::coeftest(M1, sandwich::vcovHC(M1,type='HC1'))

#>

#> t test of coefficients:

#>

#> Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|)

#> (Intercept) 4.4969959 1.6694475 2.6937 0.0074823 **

#> territory 1.6244297 0.4240554 3.8307 0.0001570 ***

#> host_resource 0.9841490 0.4425418 2.2239 0.0269364 *

#> host_mt 0.0258709 0.0072926 3.5475 0.0004540 ***

#> host_for -0.0120354 0.0067672 -1.7785 0.0763824 .

#> water -0.6005071 0.5610364 -1.0704 0.2853596

#> bord_vital -0.8091477 0.3978571 -2.0338 0.0428950 *

#> log_jointsize 0.1356500 0.1122895 1.2080 0.2280269

#> cwpceyrs -0.0404980 0.0103090 -3.9284 0.0001072 ***

#> ---

#> Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

I don’t expect you to know what this does, but I’ve pointed you in the direction of what this does on my blog. Don’t sweat those details now. Just know it’s what a lot of practitioners do in the presence of non-constant error variance (heteroskedasticity).

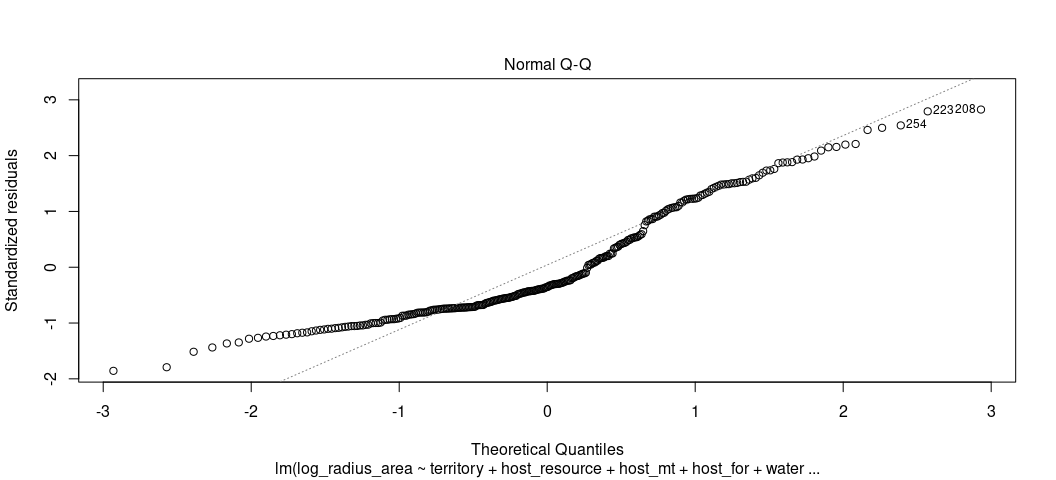

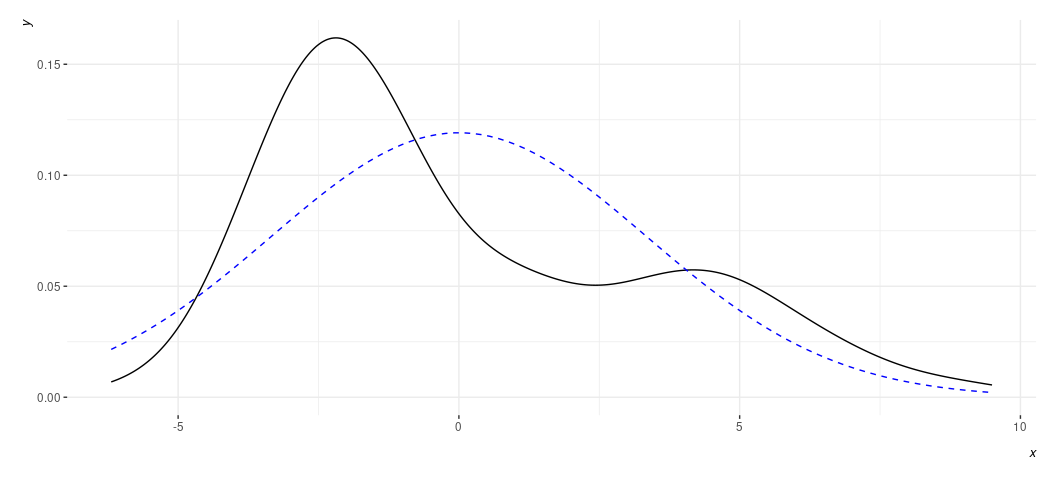

Finally, we can check for whether the residuals are normally distributed. This assumption has no bearing for our test statistics or our line of best fit, but it’s nice to estimate a model that can reasonably fit the data.

plot(M1, which=2)

rd_plot(M1) + theme_steve(style='generic')

Again, a plot like this is wanting to alert us to the “hurdle” component of the DV. Rather than have normally distributed residuals, or something reasonably approximating it, we have two such peaks in our data. Non-normally distributed residuals strongly imply a non-normally distributed DV. We already knew we had that in this case.